Iron Age Colchester was protected on its western edge by a series of defensive earthworks known as the Dykes. A dyke is a bank formed from the earth dug out of a defensive ditch. When first constructed, the banks reached up to 4m in height and the ditches 4.5m deep, so they created a formidable barrier. Over time, this form of earthwork appears to have developed for different reasons. As well as being used to protect settlements from attack by warriors in chariots or from cattle raiders, the Dykes were used to confine grazing animals. In Colchester, their sheer size and extent emphasised the importance of the settlement at this time.

Iron Age Colchester was protected on its western edge by a series of defensive earthworks known as the Dykes. A dyke is a bank formed from the earth dug out of a defensive ditch. When first constructed, the banks reached up to 4m in height and the ditches 4.5m deep, so they created a formidable barrier. Over time, this form of earthwork appears to have developed for different reasons. As well as being used to protect settlements from attack by warriors in chariots or from cattle raiders, the Dykes were used to confine grazing animals. In Colchester, their sheer size and extent emphasised the importance of the settlement at this time.

Several stretches of the Colchester Dykes are still accessible for everyone to see today. Lexden Triple Dyke and Blue Bottle Grove are well-preserved examples from the Iron Age. Gryme’s Dyke is a later Roman addition to the Iron Age system and may have been built as long as 20 years after the Roman invasion in AD 43, perhaps in response to the revolt led by Boudica, the queen of the British Iceni tribe, when the town was destroyed by fire.

In 1940, the defensive importance of the Dykes was appreciated once again when the stretch known as ‘Blue Bottle Grove’ was refortified, in expectation of an imminent German invasion.

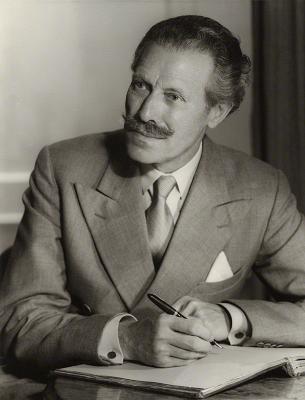

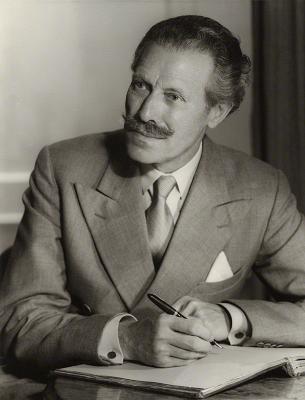

Sir Mortimer Wheeler was one of the twentieth century’s most important archaeologists. He became famous in Britain in the early 1950s when he featured on the BBC television series Animal, Vegetable, Mineral, and in this role he popularised archaeology with the British public. Prior to this, he had been responsible for the establishment of the Institute of Archaeology at University College, London, in 1934, where he assumed the position of Honorary Director. During the late 1930s and early 1940s he excavated numerous large and complex sites, including the Iron Age hillfort at Maiden Castle in Dorset. In 1944 he was appointed Director of the Archaeological Survey of India, where he focused much of his attention on the Bronze Age civilisation of the Indus Valley.

Sir Mortimer Wheeler was one of the twentieth century’s most important archaeologists. He became famous in Britain in the early 1950s when he featured on the BBC television series Animal, Vegetable, Mineral, and in this role he popularised archaeology with the British public. Prior to this, he had been responsible for the establishment of the Institute of Archaeology at University College, London, in 1934, where he assumed the position of Honorary Director. During the late 1930s and early 1940s he excavated numerous large and complex sites, including the Iron Age hillfort at Maiden Castle in Dorset. In 1944 he was appointed Director of the Archaeological Survey of India, where he focused much of his attention on the Bronze Age civilisation of the Indus Valley.

What is perhaps less well-known about Sir Mortimer Wheeler is that he carried out his very first excavation in Colchester, in 1917, at the Balkerne Gate. This gate was the western entrance to the Roman town.

Gosbecks, located about 4 km to the south of the walled town, was probably the centre of Iron Age Colchester and possibly the home of King Cunobelin.

The Romans took over the settlement at Gosbecks and built a temple, possibly dedicated to Mercury. This would have been a religious focus for the native population.

The Romans also built a huge theatre at Gosbecks in around AD 100. Gosbecks’ theatre is the largest known from Roman Britain, seating around 5,000 people. It was probably used with the temple for assemblies, speeches, religious rites and dramatic performances.

In around AD 275 the importance of the site declined. The theatre and the temple were abandoned and dismantled and the building materials were taken away and recycled.

Today, both the theatre and the temple have completely disappeared; only the outlines can be seen marked out on the ground.

The Temple of Claudius was the largest temple building in Roman Britain, an indication of Colchester’s status and the focus for the worship of the emperor and his successors. A temple already existed at the time of the revolt of Queen Boudica in AD 60 and it is referred to in the historical account of the destruction of the town. Today, only the foundations of the original temple survive below Colchester Castle.

The inside of the temple was reserved for priests to worship the spirit of the emperor; everyone else would have gathered outside in a large enclosed space known as the precinct. It is likely the precinct would have housed a statue of Claudius and an altar, approached through a monumental arch.

At the end of the Roman period, the temple may have been used as a Christian church before it fell into disuse. The whole site was largely abandoned for centuries, although shortly before the Norman Conquest a Saxon chapel was constructed among the ruins. The Normans recognised the importance of the temple site, both as a legacy of an ancient past and as an excellent location for their castle as they realised they could use the existing foundations. Today, these remains – the Vaults, as they became known in the eighteenth century – can be visited on guided tours of Colchester Castle.

The Lexden Tumulus is one of the best known and richest burial mounds in Britain. It dates from around 15 BC, in the Late Iron Age.

The Lexden Tumulus is one of the best known and richest burial mounds in Britain. It dates from around 15 BC, in the Late Iron Age.

When the burial mound was excavated in the early 1920s by Philip and Henry Laver, they found a large pit containing the cremated remains of an adult male who died at around 40 years of age. Buried alongside him was a rich assemblage of grave goods including chain mail, a folding stool, a Middle Bronze Age copper alloy axe head wrapped in cloth, rare figurines, 17 amphorae and a silver medallion of Augustus.

One possibility is that this is the grave of Addedomarus, one of the kings of Camolodunum before the Romans arrived.

The site of the Lexden tumulus is privately owned, but many of the grave goods are on display in Colchester Castle.

Iron Age Colchester was protected on its western edge by a series of defensive earthworks known as the Dykes. A dyke is a bank formed from the earth dug out of a defensive ditch. When first constructed, the banks reached up to 4m in height and the ditches 4.5m deep, so they created a formidable barrier. Over time, this form of earthwork appears to have developed for different reasons. As well as being used to protect settlements from attack by warriors in chariots or from cattle raiders, the Dykes were used to confine grazing animals. In Colchester, their sheer size and extent emphasised the importance of the settlement at this time.

Iron Age Colchester was protected on its western edge by a series of defensive earthworks known as the Dykes. A dyke is a bank formed from the earth dug out of a defensive ditch. When first constructed, the banks reached up to 4m in height and the ditches 4.5m deep, so they created a formidable barrier. Over time, this form of earthwork appears to have developed for different reasons. As well as being used to protect settlements from attack by warriors in chariots or from cattle raiders, the Dykes were used to confine grazing animals. In Colchester, their sheer size and extent emphasised the importance of the settlement at this time. Sir Mortimer Wheeler was one of the twentieth century’s most important archaeologists. He became famous in Britain in the early 1950s when he featured on the BBC television series Animal, Vegetable, Mineral, and in this role he popularised archaeology with the British public. Prior to this, he had been responsible for the establishment of the Institute of Archaeology at University College, London, in 1934, where he assumed the position of Honorary Director. During the late 1930s and early 1940s he excavated numerous large and complex sites, including the Iron Age hillfort at Maiden Castle in Dorset. In 1944 he was appointed Director of the Archaeological Survey of India, where he focused much of his attention on the Bronze Age civilisation of the Indus Valley.

Sir Mortimer Wheeler was one of the twentieth century’s most important archaeologists. He became famous in Britain in the early 1950s when he featured on the BBC television series Animal, Vegetable, Mineral, and in this role he popularised archaeology with the British public. Prior to this, he had been responsible for the establishment of the Institute of Archaeology at University College, London, in 1934, where he assumed the position of Honorary Director. During the late 1930s and early 1940s he excavated numerous large and complex sites, including the Iron Age hillfort at Maiden Castle in Dorset. In 1944 he was appointed Director of the Archaeological Survey of India, where he focused much of his attention on the Bronze Age civilisation of the Indus Valley. The

The