The Temple of Claudius was the largest temple building in Roman Britain, an indication of Colchester’s status and the focus for the worship of the emperor and his successors. A temple already existed at the time of the revolt of Queen Boudica in AD 60 and it is referred to in the historical account of the destruction of the town. Today, only the foundations of the original temple survive below Colchester Castle.

The inside of the temple was reserved for priests to worship the spirit of the emperor; everyone else would have gathered outside in a large enclosed space known as the precinct. It is likely the precinct would have housed a statue of Claudius and an altar, approached through a monumental arch.

At the end of the Roman period, the temple may have been used as a Christian church before it fell into disuse. The whole site was largely abandoned for centuries, although shortly before the Norman Conquest a Saxon chapel was constructed among the ruins. The Normans recognised the importance of the temple site, both as a legacy of an ancient past and as an excellent location for their castle as they realised they could use the existing foundations. Today, these remains – the Vaults, as they became known in the eighteenth century – can be visited on guided tours of Colchester Castle.

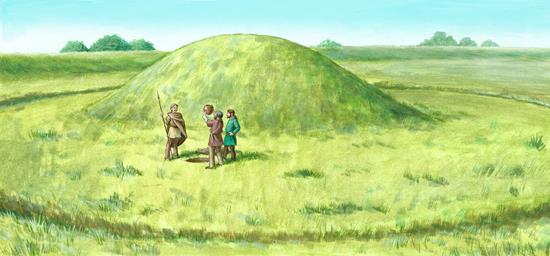

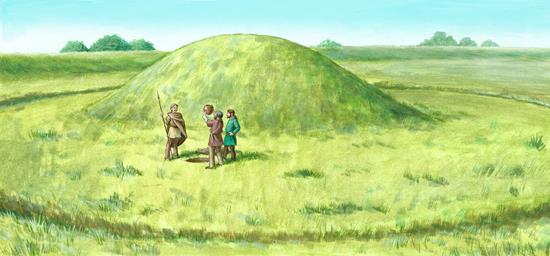

The Lexden Tumulus is one of the best known and richest burial mounds in Britain. It dates from around 15 BC, in the Late Iron Age.

The Lexden Tumulus is one of the best known and richest burial mounds in Britain. It dates from around 15 BC, in the Late Iron Age.

When the burial mound was excavated in the early 1920s by Philip and Henry Laver, they found a large pit containing the cremated remains of an adult male who died at around 40 years of age. Buried alongside him was a rich assemblage of grave goods including chain mail, a folding stool, a Middle Bronze Age copper alloy axe head wrapped in cloth, rare figurines, 17 amphorae and a silver medallion of Augustus.

One possibility is that this is the grave of Addedomarus, one of the kings of Camolodunum before the Romans arrived.

The site of the Lexden tumulus is privately owned, but many of the grave goods are on display in Colchester Castle.

The buildings of St John's Abbey were laid out in 1095 by Eudo Dapifer and the first of them completed in 1115. The cloister and domestic buildings lay north of the church, as a small hill occupied the land to the south. The abbey was burnt down in 1133 and all the workshops, which were originally on the north side were rebuilt to the south side of the church. The church was re-built on a cruciform plan, with a massive central tower and an elaborate west front flanked by south-west and north-west towers, possibly round. Late 12th century capitals, perhaps from the internal jambs of a window or from blind arcading, found near the abbey site, may have been from its church or chapter house. The abbey was dissolved in 1538.

This Norman keep known as Colchester Castle was built around AD 1078 on the foundations of the Roman Temple of Claudius. It was built in at least two main phases and its initial form consisted of a single-storey stone keep with crenellated parapet wall. During the early 12th century, the keep's outer walls were raised by at least one storey and a fore-building was added on the south side to protect the main entrance. A barbican replaced this in the 13th century. The castle's earthwork defences consisted of an upper and 'nether' or lower bailey bank and ditch (to the north, and down-slope to the town wall) with at least one entrance in the upper bailey's south-west corner. The upper bailey defences had been built by 1101. The northern and eastern arms of the upper bailey defences survive as landscaped earthworks within Castle Park. The southern arms lies just to the north of the High Street, and the western arm, below or just to the east of Maidenburgh Street. The nether bailey is possibly part of a second phase, of the late 12th century. The southern end of the eastern arm of the nether bailey survives as a landscaped ditch in Castle Park. The western arm lies below or just to the east of Maidenburgh Street. A masonry chapel and domestic buildings stood to the south of the keep. The keep was partially demolished in the 17th century.

This Norman keep known as Colchester Castle was built around AD 1078 on the foundations of the Roman Temple of Claudius. It was built in at least two main phases and its initial form consisted of a single-storey stone keep with crenellated parapet wall. During the early 12th century, the keep's outer walls were raised by at least one storey and a fore-building was added on the south side to protect the main entrance. A barbican replaced this in the 13th century. The castle's earthwork defences consisted of an upper and 'nether' or lower bailey bank and ditch (to the north, and down-slope to the town wall) with at least one entrance in the upper bailey's south-west corner. The upper bailey defences had been built by 1101. The northern and eastern arms of the upper bailey defences survive as landscaped earthworks within Castle Park. The southern arms lies just to the north of the High Street, and the western arm, below or just to the east of Maidenburgh Street. The nether bailey is possibly part of a second phase, of the late 12th century. The southern end of the eastern arm of the nether bailey survives as a landscaped ditch in Castle Park. The western arm lies below or just to the east of Maidenburgh Street. A masonry chapel and domestic buildings stood to the south of the keep. The keep was partially demolished in the 17th century.

Colchester Castle is now home to Colchester Castle Museum where visitors can explore the Roman vaults and visit the roof of the castle for panoramic views around the town. The museum's collections focus on the history of Colchester and include many very significant finds such as the Kelvedon Warrior and the 'Fenwick hoard', a collection of Roman jewellery found under the Fenwick store on High Street, Colchester.

The remains of a Roman circus , an arena for chariot racing, were discovered in 2004, during investigations in advance of the redevelopment of Colchester Garrison, approximately 450m south of the walled town.

The remains of a Roman circus , an arena for chariot racing, were discovered in 2004, during investigations in advance of the redevelopment of Colchester Garrison, approximately 450m south of the walled town.

Chariot racing was the oldest and most popular sport in the Roman world and the Colchester circus is the only example in the country. It is one of only six locations in the northwest provinces of the Roman Empire where circuses have been securely identified.

The Colchester Roman Circus is a classic example of its type - an elongated arena, approximately 450 metres long and 74 metres wide, comprising of a racing track flanked by tiered seating, known as a 'cavea', along the north and south long sides and around the curved (east) end. This would have provided perhaps as many as six tiers of seating around outside of the track, providing an estimated seating capacity for 8,000 people.

At one end of the track there was a row of eight starting gates and at the other a sharp 180 degree turn. The two long straight sections were separated by a barrier called a ‘spina’, which supported a series of decorative columns and other features, including lap counters and pressurised water features.

It was constructed around AD 125, probably on the orders of the emperor, Hadrian, who was in Britain at that time. The circus had already gone out of use by the end of the Roman period.

The building, i.e. the above-ground structure, is poorly preserved and there are no upstanding original walls or earthworks (which is the reason why the Circus was previously unknown). Today the Roman Circus Centre provides information about the site and visitors can see reconstructions of the starting gates and the seating.

The

The  This Norman keep known as

This Norman keep known as  The remains of a

The remains of a